![]()

Nov 21, 2009

By Jim Chatfield, Akron Beacon Journal

Beauty on the ground in fallen leaves, fungi

With the wonderful prolonged Indian summer-like weather, Ohio woods are still a welcome and popular (but not too populated) place for walkers and plant lovers.

The boardwalk trail at Johnson Woods Nature Preserve near Orrville, the Ledges Loop Trail in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park and the Sheepskin Hollow State Nature Preserve in Columbiana County are just a few trails I have recently enjoyed with friends and family. Also, the Ohio State University Plant Pathology Fleshy Woodland Fungi class had an outstanding fungal foray two Saturdays ago at Geneva Hills Camp south of Lancaster.

Even urban forests still show fall color, from fallen sweetgum leaves to spectacularly purpled and bronzed leaves still attached to twigs of Callery pear trees. Here are a few highlights:

Leaves

One of the students in the fungi class had a great reason for enrolling in the course. He is a forestry major in the School of Environment and Natural Resources at OSU and he loves to know what he is seeing when walking the woods.

He heeds the Chinese philosopher Krishtalka's maxim: ''The beginning of wisdom is calling things by their right name.'' While acknowledging there is ever more to learn, he said he felt he was getting to know his trees well, including identification of trees from their leaves, and was getting to know his birds; was on track to getting a working knowledge of tree insect pests; and now wanted to know the mushrooms in the woods.

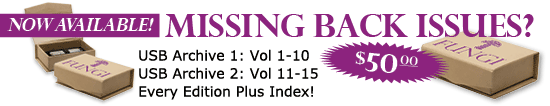

I was in synch with him on this as we embarked on our fungal foray at Geneva Hills. Our guest instructor was the wonderful editor and originator of Fungi magazine (http://fungimag.com) Dr. Britt Bunyard from Wisconsin. Bunyard is a world-renowned fungal researcher, lecturer and fungal forager. But more on that later.

What struck me on this and subsequent walks the past two weeks is how beautiful tree leaves are right now. I am used to thinking of leaves on the trees; they have a special effect at this time of year when they are on the ground and resting in ponds and streams.

It is actually a great time to see the shape of leaves as they are displayed in all their fine characteristics, after they have fallen. From tulip tree leaves floating in a pond to sweetgum leaves arrayed on lawns and sidewalks, this is a truly wonderful last hurrah for enjoying deciduous tree leaves until trees reawaken next spring.

Fungi

Oh, those fascinating fungi.

First, a reminder. Fungi are heterotrophs, unable to directly produce their own food, having to obtain it from other sources, such as plants. Plants are autotrophs, making their own food through photosynthesis.

We learned a lot on our foray from Brunyard. One of his specialties is studying and teaching about some of the fascinating multilayered webs of nature in which fungi interrelate with other organisms.

For example, on our walk we found some remnants of an ericaceous plant (in the heath family) related to the genera Monotropa and Allotropa. (Monotropa is the familiar Indian pipe, a weird, ghostly white plant in Ohio forests.) These flowering plants were once thought to be anomalies — parasitic plants, getting their food from tree roots. This is because, though Monotropa and its relatives have flowers, so surely are plants, they do not produce chlorophyll and thus do not photosynthesize like other plants. They do not take carbon dioxide and water and, with sunlight and chloroplasts in leaves, turn it into food: a carbohydrate energy source (''plants eat sunshine'').

As Bunyard pointed out, though, recent research shows that these plants, rather than being parasitic on plants are actually mycotrophs. They get their carbohydrates from fungi (the root of which is ''myco'').

Say what? Here is how it works. There are a number of soil fungi known as ''mycorrhizal'' fungi, many of which have mushrooms as their sexual fruiting bodies. These mycorrhizal fungi form a symbiosis with plant roots, known as ''mycorrhizae,'' which literally means fungus-roots.

The mycorrhizal fungus enhances mineral uptake for the plant, and the plant provides carbohydrate food to the heterotrophic fungus. Which brings us to Monotropa and its relatives.

Remember, they were once thought to be parasitic on plant roots, obtaining from them their carbohydrate energy source. In reality, they get their carbohydrate from the mycorrhizal fungus, which got its carbohydrate from trees.

What looks like a woodland scene of separate parasitic plants and mushrooms and trees is in reality a three-part symbiosis, one of many complicated webs by which organisms communicate. Ain't nature grand?

So if you marvel at stuff like finding a mushroom in the woods that is mildly toxic to eat unless it is infected by another fungus and if you want to learn which fungi are poisonous, which are edible and in which cases it depends, or if you want to learn about the best fungal culinary arts from cooking with Penicillium roqueforti (the fungus that gave blue cheese its fame) to a species of Rhizopus (the fungus that ferments soy and gives us tofu-like tempeh), check out Fungi magazine and join the growing number of afunginados.